By Michael Green

Copyright MG-July 2005

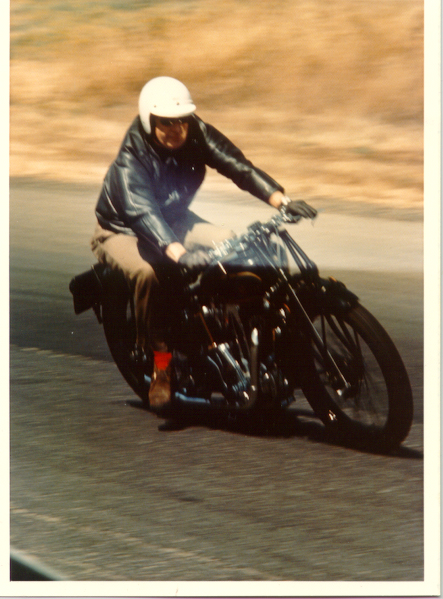

This past June I reminded my dad that this year (2005) was fifty years since his last visit to LeMans. Le Mans ’55 will go down in history for the terrible accident on the front straight. Richard was there on the pit counter when it all happened. We also talked of the new Aston team and their success at Sebring, and their LeMans debut. I did e-mail my racing resume to Pro-Drive, hoping I too could join the Aston team… no one called. In October 2005 Richard, Doreen and I did visit the Aston Team at Laguna Seca for a tour of the team and cars. Back to the story; In our last installment we covered the early 1950’s, and we will now pick-up where that story left off, at the beginning of the 1953 season and the new DB3S. Yes, that's Richard (below) on his 1929 Sunbeam 500 at Sears Point Raceway, 1977. MG

My Years with ASTON MARTIN

By Richard Green

The early months of 1953 were spent preparing DB3/4 and DB3/5 for a race we should have won, the 12-hours of Sebring in Florida. Unfortunately, Geoff Duke crashed and retired DB3/4 whilst in the lead… and DB3/4, with Parnell and Abecassis at the wheel, finished a close second to the Cunningham C4R of Fitch and Walters.

Back at Feltham, Willie Watson (who worked for W.O. Bentley) conceived the idea of making the DB3 lighter by reducing the overall size of the car. The general lack of accessibility with the DB3 was also a problem that wanted solving, for it was almost impossible to carry out any operation without removing the entire body – a time consuming task, at best.

John King, Bill James, and I worked steadily on the prototype DB3S while the remainder of the shop prepared DB3/3, 4 and 5, plus one of the lightened DB2s (XMC77) for the Mille Miglia. Eighty-hour workweeks were not unusual during this period.

DB3S/1 was complete in late March and made its first run at Charlgrove, a disused airfield we used for testing purposes. The chassis was completely new, with the original Salisbury hypoid now replaced by a new aluminum 7-1/4 inch spiral bevel unit that was produced by David Brown. With this system, we used a central slide location rather than the Panhard rod to locate the DeDion tube. There was, however, a great deal of carryover from the previous car – the suspension and braking systems, for instance, were virtually the same. I recall the time when John King and I fabricated the fuel tank brackets from scratch. They were such an odd shape that when we completed the job, the drawing office came into the shop to make the detailed drawings! We were looking for a 4% increase in overall performance at this early stage; this was achieved without problem, and we departed from Charlgrove well satisfied with our initial run.

Early April saw us en route to Italy where we made headquarters at the Casa Maggi in Calino, just outside of Brescia. This was home of Count Maggi, patron of the Mille Miglia, and driver of Alfa Romeo’s in the twenties. During this voyage we made a short detour while Fred Lown, driving a DB2 chassis that was fitted out with plywood fenders and Plexiglas windscreen, delivered this rolling chassis to Bertone in Turin. It was on then to Monza to start our preliminary shakedown tests where, for two weeks, the drivers practiced in DB3/1, now in supercharged form. These sessions took place just after dawn, with the cars returning just after lunch. This gave us time to carry out normal maintenance, and to make any modifications that were necessary. Once such modification was to install a plain old brass door-bolt into the door section itself; we had discovered that body flex under certain conditions unlatched the door! Apart from the DB2 splitting its oil cooler and fuel tank, and DB3/1 suffering a broken sub-frame on the chassis and a slipping clutch, all went well!

Fred Lown and I, accompanied by Bob Walsham and a tyre fitter from AVON’s, made tracks for L’Aquila (some 453 miles from the Start) in the transporter. Ours was the job of establishing a third refueling depot. We were next to Ferrari, and their chief mechanic, Meazza, had reserved a section of the main street for us. Just adjacent was a side street where we were able to park the transporter. Refueling in this 1000-mile event bore no resemblance to normal pit work, since the enthusiastic public were always packed tightly around you. L’Aquila was also a control point where all the cars had to stop to have their route card punched. The usual driver’s drill was to stop with all four wheels locked up and the car sliding in a great cloud of dust, and then accelerate away at maximum RPM. You could always tell the "triers" by their race number, which was, in fact, their starting time. I still recall seeing both Marzotto, the eventual winner, and Fangio (driving an Alfa 6C3000 coupe) accelerating away from the control to the wild applause of the crowds!

All our DB3s arrived and were refueled without incident, but the DB2 (XMC77, driven by Tommy Wisdom) retired in Ancona. Arrangements were such that Fred and I were to backtrack the course in an effort to collect the DB2. Some Italians told us of a British car, green in colour, stranded south of Presaro – but it turned out to be Moss’ C-type Jaguar. We arrived back in Calino in the early hours of the morning, only to find everyone tucked safely in bed!

This was the last major race for the DB3, and Parnell finished fifth, the highest place ever achieved by a British car. Parnell had driven from Florence to Brescia with a broken Panhard rod mounting, so the DeDion tube had no lateral location. On the Futa Pass the throttle cable broke, so Reg jury-rigged the system in flat-out position and completed the remainder of the race on the Lucas ignition switch! Peter Collins finished 16th with the steering rack secured to the chassis with bailing wire, while George Abecassis retired outside Florence with the same malady, broken steering rack mounts.

We left Brescia for Monza to meet Eric Hind, who, accompanied by Peter Collins father, had brought DB3S/1 from England in their Ford transporter. The test proceeded well with peter doing the majority of the driving, and we had our improvement in performance with little increase in BHP. As always, a number of flaws were quickly discovered, Professor Eberhorst had retained the inboard rear brake system, and we soon discovered (when attempting to check the condition of the rear shoes) that it was impossible the remove the drums with the spiral bevel unit in situ. A modification to the chassis was made to overcome the problem, but this was never satisfactorily resolved until the brakes were moved outboard, this solution finally being insisted upon by John Wyer.

Our experience at LeMans indicated that it was only necessary to change wheels on the left-hand side during the 24-hours, and so a jacking system was designed to enable one side only of the car to be lifted clear of the ground at any one time. A tune 2-1/2" in diameter was welded at right angles to the chassis rail, and this matched a hole of 3" diameter in the body side. Through this hole a long, pointed bar was inserted into the chassis tube by some ten inches. A long jacking lever worked on a cam arrangement, and by depressing the handle (which was parallel to the body), the car was raised clear of the ground. We tried this new system during an inspection of the front brake linings… I was removing the front brake drum with both my legs under the car, when I must have jiggled the drum too hard, the jack cam went over center, and the car came down with a crash! The rear wheel was still on, but my legs were trapped under the car. Fortunately, there was no damage to the car or to me. Poor Eric was not so lucky, however. While standing by the cockpit he was hit in the middle of the back by the jack handle, and this resulted in a trip to the local hospital. Needless to say, John Wyer had us revert to the more conventional jacking system, at the same time, we thus lightened the car by at least ten pounds by removal of the jacking tubes!

The Monza test car was fitted with a light alloy, twin plug head. Whilst Peter was driving, his lap times slowed because of the loss of some 600 RPM. The Professor, of course, had a theory regarding this loss of power, and the theory involved the structure of the plugs. He believed that the front plug of any cylinder should be of a different heat range than those in the rear; the actual cause of the power loss was a broken rotor arm in the distributor! The car failed to appear on one lap, and we found Peter sitting on the fender at the Lesmo and pointing to a very large hole in the block; a rod had broken! John Wyer was anxious to carry on with the test program, so with some modifications we installed the standard six-plug iron-head engine from one of the Mille Miglia cars and thus completed the thousand miles. We loaded the engineless DB3 into Collins’ transporter, and I drove DB3S/1 back to Feltham, arriving in early May after one of the best riders I’ve ever had! I returned home just in time for Silverstone, where the DB3’s made their final works appearance, with Parnell and Collins finishing 1st and 2nd in the 3-litre class, a great ending.

Back at Feltham, DB3S/2, 3 and 4 were under construction for LeMans, which was now six weeks away. John Wyer makes a point in his book that the DB3S failed through inadequate and hurried preparation; certainly we were all getting very weary on our 90-hour per week diet! Poor Reg Parnell was very upset at crashing his car at Tertre Rouge on the 16th lap, while the other two cars retired, one with a slipping clutch and the other with broken tappets. As a spare we had with us DB3S/1, now fitted with a new engine. Reg, always looking at the next race, wanted to drive this car in the Empire Trophy Race

Which was taking place on the Isle of Man just four days later. He drove alone across France and back to Feltham, picked up Eric Hind (still with a back problem) and continued on to his farm in Derby. Here he collected his own car, and the two of them completed the journey with Eric driving the remaining distance in the DB3S. They arrived in time for the first practice, where Reg made fastest time – a feat he repeated on the following day in the presence of John Wyer. He lost pole position to Moss in a C-Type Jaguar, but retained his former position by breaking the lap record twice in the final practice. Then, disaster struck! Eric was returning the car to the garage when a rear driveshaft universal broke. We had returned from LeMans with the transporter that Wednesday afternoon. At about 10:00pm, one for the factory police knocked on the door of my apartment and advised me that Mrs. Wyer had called the Guard House and would I please return the call. She soon put me in the picture, and asked if I could do something. I contacted Fred Shattuck (he, at least, had a phone), and around Midnight we unloaded a transporter and removed a pair of driveshafts from the LeMans cars. I then advised Jack Stirling, our Managing Director, of the plan, took XMC77, and drove through the night to Liverpool to catch the first flight, a DC3 that arrived on the Isle of Man at 8:00am. Eric and I installed the new driveshafts, and Reg, after a wonderful drive, demoralized the opposition by winning the British Empire Trophy Race at a record speed. What followed was a fair night out!

The next event was the Sports Car Race at Silverstone, which was held as a curtain raiser to the British Grand Prix. Here we beat the Jaguars fair and square by taking the first three places! Reg also ran at Charterhill in Scotland, and won the main event in DB3S/1. At this point, we had a small sideshow when all British LeMans competitors, drivers, cars, and mechanics were invited to Goodwood by the Duke of Richmond. Here, the whole entourage was met by H.R.H., the Duke of Edinburgh - a real car enthusiast, and the owner of a Lagonda.

September saw us back at Goodwood for the 9-Hour Race, which is best described as an effortless win for the DB3S cars. They finished in 1st and 2nd positions driven by Reg Parnell/Eric Thompson and Peter Collins/Pat Griffith. Roy Salvadori came into the pits after completing 56 laps and complaining that he was unable to select gears at the chicane. John King and I made a cursory check of the gear lever, and then John opened the hood… he was immediately sprayed with hot water; a connecting rod had punched a hole through the block! Poor Roy, he never was really very mechanically minded. I looked after the Collins/Griffith car during the race and, apart from scheduled pit stops, there was little to do.

The Tourist Trophy at Dunrod (Ireland) was virtually a repeat of the previous months’ events; the DB3S finished 1st and 2nd against stiff opposition. Unfortunately, Dennis Poore had his goggles shattered by a stone and this caused him to crash while lying in third place. I recall vividly an episode that took place in the shop during the preparation of the cars. The T.T. Regulations stated that at the first wheel change, the spare that was carried in the car had to be used. The DB3S was never designed such that the spare wheel could be removed easily – it virtually meant that one had to take off the body in order to accomplish this very fundamental task. We did a number of fast modifications to the bodywork and seats, which enabled us to remove the wheel quickly, and requested the drawing office to sketch a quick-release bracket to secure this wheel in place. Not liking their design, we quickly copied the quick-release bracket that held the spare wheel on a Type-44 Bugatti we found in the car park! It was a much neater solution entirely!

The last race of 1953 was a twelve-hour event at Casablanca. We had not entered as a team, but were represented by a private owner, Michael Sparken, with Roy Salvadori doing the majority of the driving. Bill James and I prepared Sparken’s car, a DB3 which was fitted with a coupe body by Vignale. This quickly became known as the "Parker-Kaylon Special" because of the multitude of sheet metal screws used in its construction.

During the ’53 season, we had, after extensive modifications, reduced the weight of the DB3S by 167 pounds from that of the DB3. By enlarging the inlet valve by two millimeters to 1.594" and changing the camshaft lift, we increased power to 180 BHP at 5500 RPM. And so concluded the 1953 season. The first major race for the DB3S had been a disaster, but the Tourist Trophy was a grand finale for our new car, which had won every race, apart for LeMans, that it had been entered for! Now we look forward to 1954….

Join us next time when Richard relates his time with the Aston Martin Works Team, and how Doreen (Sherwood) Green learned to drive in a DB3S. For more photos visit www.offroadexperience.com/wcb and click on Aston Martin.